A tale of two intellectual paradigms

People of Indian origin have excelled in the role of executives, while those of Chinese origin have outshone others as visionaries. In recent decades, Indian professionals have reached the pinnacle of leadership in multinational corporations. From Microsoft to Google and IBM, these "administrators" symbolize India's rising profile in global corporations' boardrooms.

Chinese visionaries, on the other hand, have created Alibaba, Huawei, BYD, Byte-Dance (TikTok), and Tencent (WeChat). From high-speed railway and other technological infrastructure, and from quark to quantum physics, Chinese visionaries have reached many a milestone at home.

This raises a puzzling question: Why have the Indian managers flourished abroad, but not at home, and why do visionaries achieve far greater success at home than abroad?

This contrast is not just about where success is achieved but the form it takes. That India excels in producing global managers could be traced back to its colonial past where "viceroys" served the sovereigns of Great Britain. Visionaries foster institutional entrepreneurs and build structures from the ground up.

The rise of Indian executives in multinational corporations is often attributed to their talent and education. But underlying this is a civilizational script shaped by colonial governance. India's administrative class, once trained to serve imperial institutions, passed on a legacy of institutional conformity, managerial competence and comfort with hierarchical structures. Many Indian professionals today mirror these qualities, excelling in environments that reward precision, discipline and alignment with shareholder interests.

This heritage is reinforced by India's elite educational institutions, which emphasize problem-solving, data analysis and technical rigor. These institutions offer a meritocratic but narrow pipeline into global corporate and academic ecosystems, particularly in the science and engineering fields.

Academics have their own trajectories. Scholars of Indian origin dominate in Western universities, taking up managerial and academic roles.

Yet hardly can we pinpoint a dominant theoretical framework proposed by Indian executives at home or abroad, except for a few dots here and there. This mirrors their corporate acumen both as managers of companies and managers of journals: capable stewards of institutional performance, but not necessarily institutional vision.

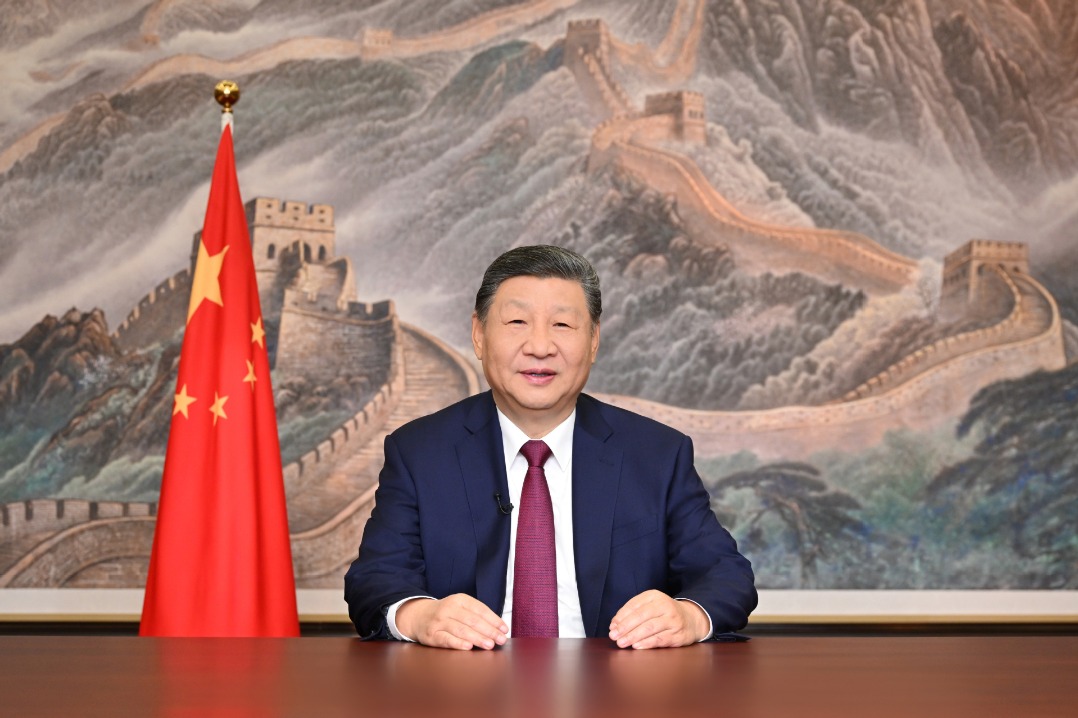

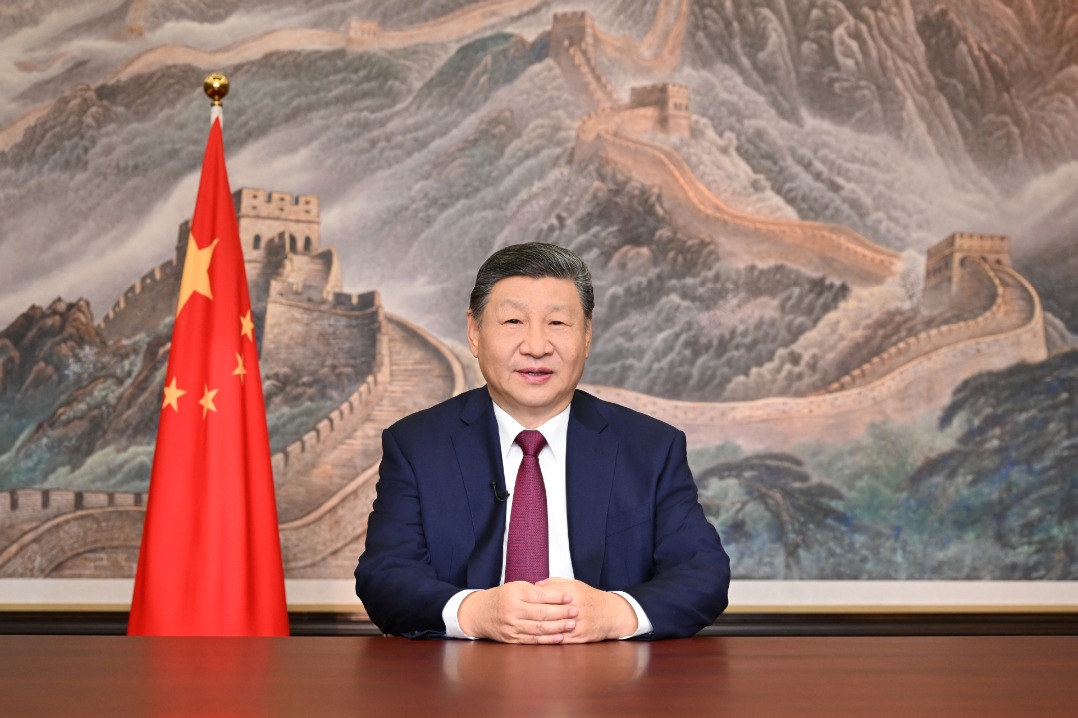

The trajectory of the Chinese visionaries offers a striking contrast. While fewer Chinese professionals have reached the top of Western institutions or corporations, many have achieved prominence at home by building institutions from within. This is particularly evident in the technology, education, and infrastructure sectors, where the visionaries have developed competitive alternatives to Western models. Visionaries have begun to globalize institutions such as the Belt and Road Initiative.

This success stems from an ethos of institutional entrepreneurship. Visionary professionals are often embedded in long-term planning ecosystems, public-private partnerships, and government-supported innovation clusters. Their influence is not always individually visible, but collectively transformative.

This domestically focused model relies less on individual charisma and more on systemic coordination. It also reflects a different relationship to narratives and communication. Chinese professionals tend to operate "below the narrative line", embracing modesty, indirect persuasion, and institutional continuity over personal acclaim. Their narratives are often embedded in State-driven or organizational scripts rather than personal branding.

In line with its cultural traditions, rooted in rhetorical diversity, debate and negotiation, India has produced professionals who are adept at storytelling, framing and strategic persuasion about things that do not exist. These narrative skills are essential in executive leadership, academia, and diplomacy, where success often hinges on how ideas are presented, not just their content and material value.

For Chinese visionaries, the narrative has a different scope of stakeholders — inclusivity, social well-being, and people above capital. The visionaries' rhetorical fluency reflects their subtler communication style. Where a viceroy often presents expansive visions and can sell a future that does not exist, the visionary presents the achievements of the past.

The scope of a visionary's audience is the domestic institutional strength, minimization of the overextended gap between narratives and material realities. These visionaries have helped build world-class infrastructure and promoted equitable education, meaning the visionaries' narrative advantage has translated into domestic transformation at scale, which is missing among the Indian executives.

The contrast between India's global executives and China's domestic visionaries is not about cultural superiority or developmental speed, but about cultivational versus foundational skills; transformational versus institutional acumen; structural versus generational wisdom. It is about the disposition of hidden persuaders — the habits of thought. One excels in operating within the principal or shareholders' system; the other operates in building a homegrown framework of systems.

This divergence raises a larger question for emerging economies: should the goal be to master existing institutions in distant lands or to author new ones in the proximity of one's home? Can a nation create leaders who are both effective stewards and generative builders?

As the world confronts institutional voids in climate governance, healthcare equity, and digital regulation, success will require more than operational competence. It will demand imagination, risk-taking, and the ability to build institutions that do not yet exist. That is the work of visionaries.

The author is a professor of innovation studies at Liaoning University.

The views don't necessarily reflect those of China Daily.