The unforgotten artisans of the Forbidden City

Excavations at the site of the former Imperial Workshops reveal a treasure trove of artifacts, showcasing the craftsmanship that once flourished there and the grand picture of Beijing as the capital city, Wang Kaihao reports.

"The workshops thus served as a dynamic platform for the integration of different techniques and artistic traditions," Xu adds.

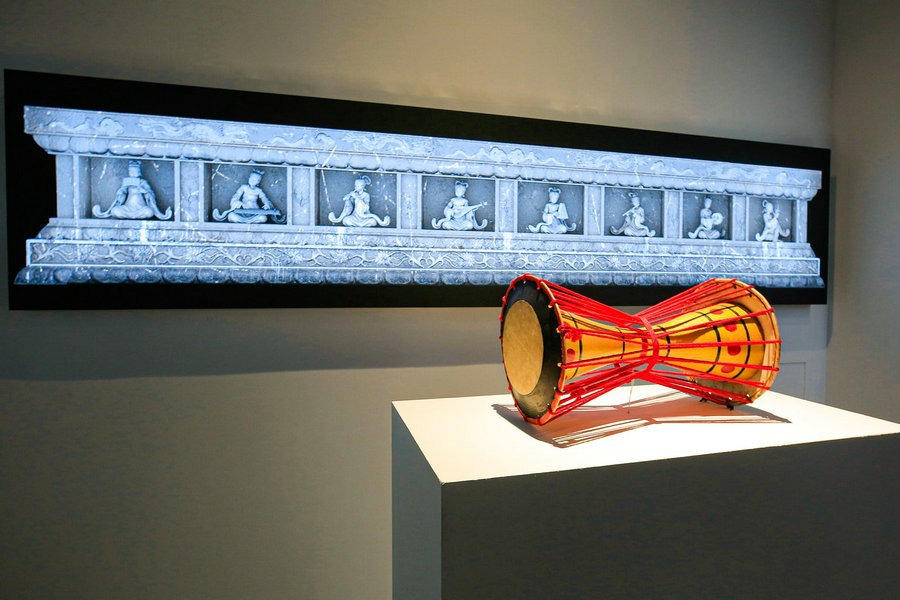

Though Jingdezhen in Jiangxi province was the major production base for imperial-use ceramics, some porcelain pieces were sent to the Forbidden City for further decoration. At the exhibition, some recently unearthed broken porcelain is juxtaposed with artifacts with the same patterns that have remained intact and are in the Palace Museum's collection.

However, according to Wang Guangyao, a veteran porcelain researcher at the Palace Museum, finding these broken pieces is uncommon, because the rigid management system of Qing imperial porcelains demanded that once a royal porcelain vessel was broken in use, its shards would be sent back to the warehouse. Experts therefore speculate that the porcelain fragments found during the excavations were accidentally broken during the manufacturing process and so left in the workshop.

"Due to the archaeological work, you can also learn about the artisans' everyday life," says Xu. "Unearthed porcelain pieces from folk kilns from across the country, stone artifacts, animal bones and other relics can tell us how they lived and what they ate."

An unearthed tool made from an animal bone and used in a drinking game shows how artisans spent their leisure time. The processing of other bones reveals that the imperial craftsmen used the same techniques on items for their own use as they did for objects used by the royal family. Alternatively, they may have just wanted to practice and refine their skills, even when not working.

"We get a vivid view of everyday life within the Qing imperial palace," says Dong Xinlin, deputy director of the Institute of Archaeology at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. "Thanks to these findings from the craftsmen, we see more than cold archaeological ruins. The artifacts become lively storytellers, and the Forbidden City demonstrates its other face as a vibrant society."

A layered city

Nonetheless, excavations at the site are concerned with much more than just the Qing workshops.

"Beijing is a typical example of a historically layered city," Xu says. "Centuries of structures and remains overlap from the past to the present, particularly densely within the palace walls."

Guided by the principle of "minimal intervention", Xu and his fellow archaeologists seize rare opportunities like the Imperial Workshops site to examine the traces of evolution and thus reconstruct the historical layers long before the place became a complex of Qing workshops.

A Buddhist sanctuary, Dashan Dian (Hall of Great Virtue), once stood on the current spot of Cining Gong in the early Ming Dynasty (1368-1644). However, like people today who redecorate and renovate their homes, the emperors who lived in the Forbidden City also changed the layout of the imperial palace.

Emperor Jiajing of the Ming Dynasty was one such active renovator and during his reign, the layout of Beijing's imperial city was dramatically altered. As a pious believer in Taoism, he eventually demolished Dashan Dian and instead built Cining Gong for his mother, although studies show that warehouses existed in the later Ming period on the current Imperial Workshops site.

The past few years' research deep underground at the site has also yielded valuable evidence about the building techniques employed at the Forbidden City during the early years following its completion in 1420.

Remains of three early Ming structures and a wall within the site have been identified.

"The findings provide a compelling glimpse into the grand and sophisticated underground engineering that supported the construction of the Forbidden City," says Xu.

The exhibited bricks, tiles and other constructional components act like jigsaw puzzles, helping people imagine the splendor of these palaces.

Yet, more surprises have been uncovered; components of imperial architecture from the earlier Yuan (1271-1368) and even Jin (1115-1234) dynasties have been unearthed at the site. These new findings are also on show at the Imperial Workshops exhibition.

Xu explains that the concentrated presence of this early architecture on the Imperial Workshops site also reflects a systematic process during the construction of the Forbidden City — bricks and tiles from earlier dynasties were gathered and buried as foundational fill, over which new palaces were built.

"Subsequent reigns continued to build atop these early foundations, gradually raising the ground level to what we see today," he says.

"However, compared with the answers it provides, the excavation raises more questions. Five years of research is only the beginning."

Dong says that the new round of excavation not only increases the timeline of the Forbidden City studies, but also provides pivotal, archaeological evidence for Beijing's status as a national capital city.

"Such an exhibition is also a meaningful move to share academic achievements with the public," he says. "People will thus deepen their understanding of the Forbidden City."

In the gallery, an 18th-century antique clock from the Palace Museum's collection may remind people of the golden age of the Imperial Workshops, but more importantly, it reminds people of the flow of time.

However much time passes though, the brilliance of the civilization unearthed from the Forbidden City site will remain undimmed for centuries to come.

Contact the writer at wangkaihao@chinadaily.com.cn