Coding the law for smart governance

Editor's note: China's rule of law serves as a cornerstone for deepened international cooperation and an essential safeguard for common development. China has worked to strengthen the alignment of laws, policies and standards, and to establish cooperation mechanisms for cross-border dispute resolution and to promote high-quality development. Four experts share their views with China Daily.

The transition of China's economy from the production boom of the industrial era to the transaction explosion of the digital age is posing new challenges. Artificial intelligence has reshaped industrial boundaries, big data has redefined market competition logic and blockchain has restructured trust mechanisms. These transformations demand legislation that takes into account the dynamics of the digital era.

At the 34th group study session of the Political Bureau of the 19th Central Committee of the Communist Party of China in October 2021, Xi Jinping, general secretary of the CPC Central Committee, underscored the need to improve laws, regulations and institutional mechanisms to modernize China's governance of the digital economy.

China's digital economy has reached massive scale, with its platform economy, digital payments, and AI ecosystem leading the world in both growth speed and market coverage. This enormous growth demands that governance principles be firmly grounded in China's unique national context.

Over more than a decade of legislative evolution, the principle of inclusive and prudent regulation has emerged as a cornerstone of China's approach to the digital economy. It consists of two complementary dimensions: "inclusiveness", which provides a legal observation period to incentivize innovation in the digital economy; and "prudence", which focuses on risk prevention and sets safety boundaries.

The application of this principle is evident in laws relating to the digital economy. For instance, the 2022 amendment to the Anti-Monopoly Law explicitly added "encouraging innovation" as a legislative goal, targeting monopolistic actions that leveraged data, algorithms and technological advantages. It also laid down a framework for the procuratorate's public interest litigation to ensure broader social protection.

Similarly, the Private Sector Promotion Law, China's first comprehensive legislation safeguarding private enterprises, elevates digital economy innovation to a matter of legal guarantee. The law integrates data-market allocation rules with incentives for innovation. Ongoing legislative efforts are also being guided by this principle, aiming to secure the operational safety of the digital economy while fostering its development.

In cutting-edge fields such as AI, legislation needs to promote high-quality development but also ensure high-level security. Rigid regulation tends to suffocate innovation, while lax oversight breeds instability. Given the technological complexity, what is needed is a flexible approach that promotes prudent, unified regulation while avoiding innovation suppression or regulatory mismatch.

China's adaptive governance approach balances innovation, risks and public interests. It has shaped what is known as the platforms-data-algorithms paradigm, a new analytical framework for understanding digital governance.

Platforms act as legal actors, data functions as legally recognized assets, and algorithms as behavioral engines that shape new legal relationships. Regulatory measures across these three dimensions are distinct yet synergistic, reflecting the "Chinese wisdom" of the inclusive and prudent principle honed through years of legislative practice. Together, they form the necessary analytical framework for digital jurisprudence.

In platform governance, the inclusiveness of the principle fosters innovation and open ecosystems while prudence prevents dominant players from harming consumer interests. China has ensured space for new entrants through diverse protective measures. It has also encouraged healthy competition by allowing platforms a defined period to develop differentiated models.

For instance, e-commerce practices like "pick one of two", or forced exclusivity, were strictly regulated, while legitimate marketing techniques were allowed. Similarly, in online music, exclusive copyrights that restricted competition were addressed through licensing reforms. In data governance, the principle promotes data benefit-sharing and stakeholder participation while ensuring security and preventing exploitation from information asymmetry.

Moving beyond the industrial era's rights-based paradigm, digital governance needs an interests-based paradigm guided by the principle. This shift enables a new model of value distribution that is based on law-based regulation, shared participation, needs-based access and benefit-sharing. It recognizes that data value is co-created by multiple parties, rejects exclusive ownership claims and legally safeguards stakeholders' inputs and outputs. In settling data-related disputes, regulators should pursue diversified remedies that balance data flow, innovation and market order. This ensures equitable interest allocation while avoiding the risks of both under — and over-protection.

In algorithm governance, the principle fosters the integration of algorithmic technology with regulation while guarding against discrimination or black box issues that harm public interests.

Industrial-era static legal texts are ill-suited to the dynamics of the digital economy, risking regulatory lag or overreach. Instead, a dynamic governance model that merges legal rules with technological tools is needed. Embedding regulatory technology enables full traceability of data flows, ensuring free movement under inclusive innovation while pinpointing risks for prudent oversight.

For new digital entities, such as large AI foundation models, one-size-fits-all rules should be avoided. Scrutiny of algorithm decision-making, training data use and output fairness must be strengthened, guiding healthy digital ecosystem development in line with technological evolution.

The views don't necessarily reflect those of China Daily.

Today's Top News

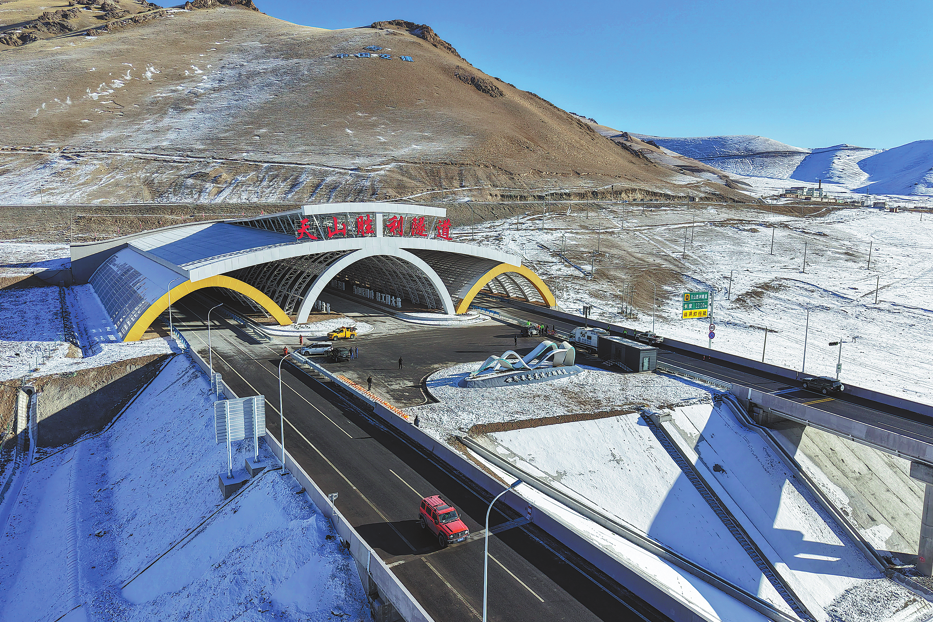

- High-speed rail mirror of China's modernization

- China will deliver humanitarian aid to Cambodia

- The US 2025: a year of deep division

- China to expand fiscal spending in 2026: finance minister

- China's finance minister pledges expanding fiscal spending in 2026

- CPC leadership meeting urges steadfast implementation of eight-point decision on improving conduct