A cup full of meaning

The character for tea embodies philosophy and heritage, proving language can be steeped just like leaves, Zhao Xu reports.

For many of the billions of tea drinkers around the world, Chinese tea is no stranger. Yet, few realize that the character "茶", meaning "tea", carries within its strokes the philosophical spirit that has anchored the Chinese people's enduring passion for the drink since it was first brewed in the 2nd century BC.

"The character has three parts — the upper, middle, and lower," says Shi Linlin of the Center for Language Education and Cooperation, an agency under the Ministry of Education dedicated to promoting Chinese language education and cultural exchange worldwide.

"The upper and lower components represent grass and wood respectively, while the middle stands for a person," she continues. "A figure standing between grass and wood evokes the image of a tea-leaf picker. If you think about it, humans savor tea and are nourished by it — the very essence of nature, as the Chinese believe."

As Shi spoke, she stood at the center of a mini-exhibition on China's tea culture, distinguished by a subtle yet clever linguistic focus often missing from similar displays. "Culture provides an entry point to language learning, and we ensure it is presented with an outsider's perspective," she explains, pointing to the exhibition's note on how used tea leaves can be used in papermaking — a sustainable idea that broadens its appeal.

The exhibition was part of the World Chinese Language Conference, held in Beijing from last Friday to Sunday. Drawing participants from around the world who are closely involved in Chinese language learning and teaching — many of them heads of Confucius Institutes, a Chinese educational organization that promotes Chinese language and culture abroad — the event offered a rare opportunity for story-sharing and provided insight into how language learning can be enriched through cultural context, innovative teaching methods, and dialogue.

"Strong family ties — that's what I find most endearing about Chinese culture," says Alessandro Tosco, Italian director of the Confucius Institute in Sicily, a region of Italy renowned for its extended family networks, multi-generational households, and enduring traditions that deeply shape local life.

A researcher of Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368) Chinese opera, Tosco draws careful comparisons between the operatic traditions of China and Italy, focusing on the differences between Chinese and Italian tragedies, the latter rooted in ancient Greek theater. "What I've found is that Chinese tragedies, deeply influenced by Buddhism and the concept of cyclical life, soften the weight of the drama while imbuing it with a sense of resilience," Tosco explains. He ensures that his organization runs events on two tracks — one for general language learners and the wider audience, and another for academics engaged in deeper scholarly exchanges.

"With language learning, you know where it begins, yet rarely where it will end," says Tosco, who has ventured into an academic path few have dared to tread.

"Italy is a country with a rich artistic tradition, which makes it naturally receptive to Chinese culture, itself deeply rooted in artistic and cultural heritage," says Wang Qin, the Chinese director of the Confucius Institute in Sicily. Typically, a Confucius Institute has both Chinese and local directors and is established within a local university, with support from a Chinese partner university.

Wang says last year, the institute organized an event in which every participant had their name written in Chinese calligraphy. "More than 30,000 people took part, which is quite remarkable given that the area is not particularly densely populated," she says.

"Many have regarded Chinese calligraphy as part of the broader Chinese tradition of ink-and-brush painting, which is precisely how our ancestors perceived it," she continues, citing a theory clearly articulated by leading literati artists from ancient China: "Painting and calligraphy share the same origin".

Another whose fascination with Chinese culture led him to learn the language is Oliver Harding, director of the Confucius Institute in Sierra Leone, one of the few English-speaking countries in West Africa. "I am a musician and painter who was captivated by Chinese music before I came to appreciate the country and its language," says Harding, who has since learned to play several traditional Chinese instruments. Both Harding and Tosco were in Beijing for the conference.

According to Wu Cui, the Chinese director of the Sierra Leone institute, Chinese language learning has surged across Africa, driven largely by employment opportunities created by Chinese companies on the continent — firms keen to recruit local staff fluent in the language and familiar with Chinese culture and business etiquette.

"For the past 13 years, since the institute was founded in 2012 as the first of its kind in West Africa, we have offered courses to more than 30,000 learners at all levels of education — including military academies. Many of them have gone on to become Chinese language teachers themselves," she says. "At present, 86 countries around the world have incorporated Chinese into their national curricula, allowing students to study the language consistently and progressively."

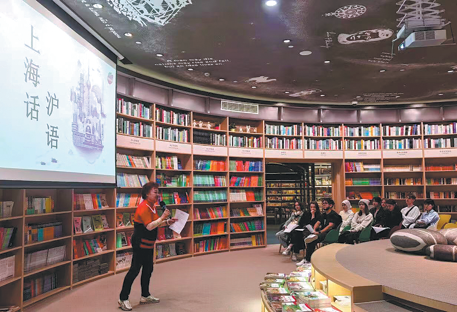

Over the course of their studies, many have traveled to China, with Shanghai — an international metropolis renowned for its openness and inclusivity — ranking as their top destination. "At the peak of our international enrollment, before the COVID-19 pandemic, we hosted more than 5,000 international students each year. We have now recovered to about 80 percent of that number," says Chen Zhuofen of Shanghai International Studies University.

One of China's leading institutions for language studies, SISU has long been a gateway for Chinese students eager to engage with the world. Today, it stands among a growing number of Chinese universities offering foreign students the opportunity to experience the country — linguistically, culturally and beyond.

"These students come from more than 100 countries," says Chen, who attended the conference to promote the university's wide range of programs. These include both full-degree courses and short-term programs offered year-round, all designed, in Chen's words, "to give students a real taste of Shanghai — its energy and rhythm" — as a natural extension of their language learning.

"We take them to companies such as Huawei and Shanghai-based automakers to give them a glimpse of Chinese industry; we also bring them into nearby neighborhoods to see firsthand how local communities actively engage non-Chinese residents. While studying in Shanghai, they are not confined to campus — they become part of the city's fabric, a community that thrives on openness and exchange," says Chen. "Our largest groups of international students are from South Korea and Russia; geographic proximity and strong trade relations certainly play a role. But when they begin to share their stories, it always comes back to culture."

Chen recalls one student remarking that Chinese, with its four tones, seemed to unfold like music. Another became so enthralled by Chinese television dramas from the 1990s — a decade of profound social transformation — that she eventually translated many of them into her native Italian. "Just recently, a Russian student donated a table tennis table to the university — a nod to a sport he came to love in China," says Chen. "Now married and building a life in China, he hopes one day to teach the game to his children."

Reflecting on the next generation, Chen notes a rising tide of overseas Chinese sending their children back to immerse themselves in the language and culture of their forebears. "We call it 'searching for the roots'," he says. "After years of forging lives far from home, these immigrants are turning back, determined that their children reclaim what they have missed so far — a living thread that ties them to the land of their ancestors."

History has never failed to leave its mark. Among the eight Confucius Institutes SISU has helped establish, one stands in Samarkand, Uzbekistan — an ancient Silk Road crossroads. It was along this great web of overland routes, as well as the mountain paths later known as the Tea-Horse Road linking Yunnan and Sichuan provinces to the Xizang autonomous region and beyond, that China's prized tea first traveled westward. Maritime trade would later carry it even farther.

Tea's journey was not only of leaves, but of language. The global variety of words for tea — tea, the, te, and chai — mirrors the routes by which it spread. The Mandarin pronunciation cha moved across Central Asia, the Middle East and Russia via the Silk Road, evolving into chai. In contrast, coastal dialects in Fujian and Guangdong used the form te, which was carried by sea through ports frequented by Dutch traders and into Europe. Thus, languages supplied by land inherited versions of cha, while those supplied by sea adopted forms of te — a linguistic map of ancient trade etched into the modern vocabulary of tea.

"A single word can throw open a window onto the vastness of history — reminding us that to tell China's story is, inevitably, to tell the world's," Chen says.

The mini tea-culture exhibition on view at the conference included a panel of Chinese sayings — ancient and modern — centered on tea. One reads, "Tea leaves open themselves in hot water; the mind, too, must loosen its grip on trouble."

Another offered a gentle reminder of tempo: "Food may be taken in haste, but tea must be savored slowly — that is the Chinese way."

Today's Top News

- China warns Japan against interference

- Nation's euro bond sale shows investors' confidence

- No soft landing for Tokyo's hard line

- Commerce minister urges US to increase areas of cooperation

- Strong demand for China's sovereign bonds signals global confidence

- Ministry urges Japan to 'maintain self-respect'