China, US can compete and cooperate on AI

Both the United States and China have made artificial intelligence (AI) a national priority. While Washington has launched its AI Action Plan to accelerate AI innovation and adoption across the US economy, Beijing has identified AI as a central component of its strategy for developing "new quality productive forces", a goal emphasized in the upcoming 15th Five-Year Plan (2026-30) period. The two countries are competing head-to-head for technological leadership, not only in model development but also in critical AI-enabled applications such as biotechnology, advanced materials and robotics.

This competition to lead the next technological frontier is natural and healthy because it drives progress, efficiency and scientific discovery. But competition in capabilities does not preclude cooperation on guardrails.

AI safety — the effort to ensure that systems work as intended and do not create dangerous spillover effects — should be an area for limited but deliberate cooperation between the world's two AI superpowers. The reason is straightforward: some AI failures stay within borders, but others do not.

An unsafe autonomous vehicle is a domestic problem. If a self-driving car malfunctions in Shenzhen or San Francisco, the damage is local. Each country can handle those risks through its own regulations and liability systems. The same goes for biased algorithms, privacy issues or the use of deepfakes in domestic politics.

But certain categories of AI risk have negative externalities that cross borders. A model that makes it easy to design a biological or chemical weapon or automate cyberattacks doesn't just endanger the country it was built in — it endangers everyone across the globe. These are strategic safety issues, not commercial or consumer concerns. Neither the US nor China benefits if the other side makes a mistake in handling them. A major misuse or technical failure would invite global backlash, pressure for sweeping restrictions and potentially duplicative testing requirements by third countries that slow progress for both sides.

That's why both countries should cooperate, maybe not on AI regulation, but on research and data related to risk detection, evaluation and incident response. Understanding how cutting-edge frontier models can be repurposed for harmful applications, or how they can fail in ways that cascade through digital systems, requires substantial experimentation and technical analysis. Both sides already invest in this kind of work domestically. Joint efforts and more information sharing could reduce redundancy, improve coverage and clarify which risks require containment measures.

This does not mean shared rules or harmonized laws. The US and China will continue to take different policy paths based on their own institutions and political systems. But the underlying science of AI safety — how models behave, how they can be stress-tested and how incidents can be identified and analyzed — does not need to be duplicated in isolation. Shared baselines make everyone's work more efficient and reduce unnecessary fragmentation.

There are models for this kind of cooperation. During the Cold War, US and former Soviet Union scientists engaged in lab-to-lab collaboration on nuclear material security and reactor safety. The two governments remained geopolitical rivals, but their scientific institutions found opportunities to share technical methods to prevent accidents. The logic was simple: when the safety risks affect everyone, preventing accidents is in everyone's interest. The same logic applies to AI. As these systems become more capable and widely available, ensuring their safety becomes a matter of shared security, not national preference.

A practical path forward would begin with shared incident tracking and vulnerability reporting. When an AI system violates safety expectations, such as producing malicious code, those events should be documented and communicated through technical research channels. Researchers can compare data on failure modes, benchmark evaluation tools and identify where new testing methods are needed.

Another step would be joint red-team exercises — controlled tests where researchers deliberately probe advanced models for misuse potential. These could be conducted under academic or multilateral frameworks with strict intellectual property protections. Cooperation could extend to research on detection and containment techniques — how to prevent models from being modified to bypass safeguards, how to identify model leaks and how to evaluate the security of model hosting environments. None of this work requires trust or political alignment, only technical competence and coordination.

Many global AI governance initiatives mistakenly assume that countries will converge on a common approach. History suggests otherwise. Nations have long made different moral and legal choices in emerging technologies, such as genetically modified crops, gene editing and stem-cell research. There was never a single global treaty governing those technologies. Instead, countries adopted their own rules.

This approach balances realism with responsibility. The US and China will continue to compete for leadership in AI innovation and commercial deployment in global markets. But they can also recognize that preventing cross-border harm from unsafe AI systems is in the interest of both nations. Neither country benefits if accidents undermine confidence in the technology itself.

Strategic AI safety — ensuring that advanced AI remains stable, predictable and secure — should be treated as a shared goal, much like nuclear reactor safety or pandemic surveillance. The competition to build more capable systems will continue. But cooperation to prevent cross-border harm is simply common sense.

The views don't necessarily reflect those of China Daily.

Today's Top News

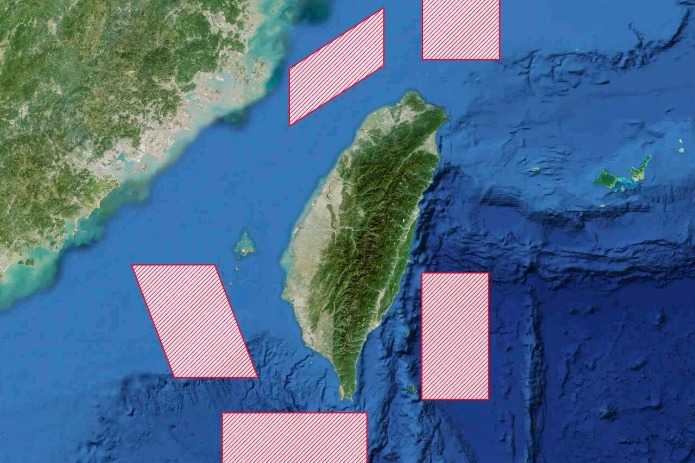

- Drills demonstrate China's resolve to defend sovereignty against external interference

- Trump says 'a lot closer' to Ukraine peace deal following talks with Zelensky

- China pilots L3 vehicles on roads

- PLA conducts 'Justice Mission 2025' drills around Taiwan

- Partnership becomes pressure for Europe

- China bids to cement Cambodian-Thai truce