An oasis of time and memory

Dunhuang Museum is a wellspring of history and culture on the edge of one of our planet's most foreboding deserts, Erik Nilsson and Hu Yumeng report.

Command and control

This inspired Han Emperor Wu to dispatch general Huo Qubing to reclaim this vital choke point between the Qilian Mountains to the south and the Mazong and Heli ranges to the north. Consequently, Dunhuang prefecture was officially established in 111 BC as a sanctuary from the brutalities of nature and humankind.

Emperor Wu commanded the construction of an immense defensive and administrative network — stretching over 2,000 kilometers, from the Yellow River's silty banks to Dunhuang's dusty periphery. Builders erected a stretch of the Great Wall that threaded together a patchwork of forts, beacon towers and ramparts to defend the prefecture and secure Hexi, fending off invaders while beckoning traders.

Models at the museum show how these structures were assembled using local materials. Laborers stacked poplar logs and slathered yellow clay churned with sand onto bundles of tamarisk and reeds, reshaping the earth under their feet to redefine the empire's horizon as far as the eye could see.

These soldiers' footprints have long since blown away in the sands of time, but their footwear — cotton, hemp and fur socks — has marched across centuries and stands still in the museum today.

They're crude fabrics compared with the exhibits of Han silk and brocades that these border guards protected with their very lives.

The sweat spent to feed Hexi's garrisons can still be imagined dripping from the displays of a Han-era millstone, bronze plow and other hand tools wielded by the soldiers-cum-farmers who cultivated the state-owned croplands that sustained the troops.

Likewise, the bloodshed that fertilized the empire's dominion feels visceral in the exhibits of iron swords, crossbow triggers and bronze arrowheads once wielded by Han watchmen.

Dunhuang served as a threshold of multiple dualities. It was the last outpost for those departing westward and the first intake for those trekking east from the Taklimakan Desert — whose name translates as "Place of Abandonment". It was here that caravans, having endured the barren wilderness, would sip from the fountainhead of civilization before stepping into the empire.

Heritage as cargo

Their most precious cargo was invisible, even unintentional — but world-changing.

The camels that plodded along the Silk Road carried not only goods and people but also ideas and beliefs, positioning Dunhuang as an intersection of commercial and cultural crossroads.

These civilizational exchanges wrought intangible treasures that outlasted most physical commodities, whose surviving specimens are rare enough today to warrant glass-encased displays.

Physical expressions of such cultural concepts include exhibits of clay unicorns and bronze tortoises sculpted during the Wei (220-265) and Jin (265-420) dynasties, a Jin-era bone ruler and blocks engraved with such motifs as a tiger, a maidservant clasping a spoon and a manservant clutching a broom.

The most invaluable treasures were not just artistic but spiritual.

Buddhism ranks among the most transformative and durable concepts to undertake the eastward pilgrimage along the Silk Road. It not only shaped Dunhuang's society but reshaped the very land itself. The force of faith didn't just move mountains but, in the case of the Mogao Grottoes, reconfigured them.

This cave complex is literally a dream come true. It's said that a monk named Le Zun was enraptured by a vision of 1,000 Buddhas, which inspired him to set a chisel against a cliffside of the Singing Sands Mountain.

Over the following millennium, Dunhuang's devout whittled a honeycomb of over 700 caverns — libraries, temples and galleries — inhabited by statues and murals, embodying a heavenly host in an underground otherworld.

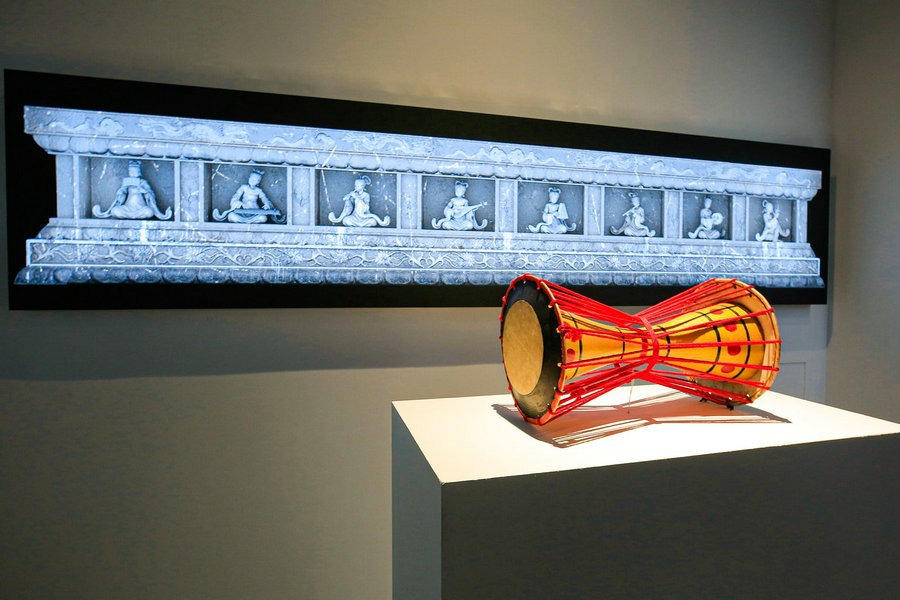

Dunhuang Museum's visitors can step into a reincarnated time capsule — a fullscale replica of Mogao Cave No 45, a cavity crowded with sculptures and frescoes rendered during the Silk Road's Tang-era pinnacle.

Access to the actual cave is restricted, but visitors to this facsimile can linger, explore and photograph its glories uninhibited.

The grottoes' subjects attest to Dunhuang's multiculturalism, as do the diverse currencies that helped finance them.

A numismatic display shows the Arabian gold, Persian silver and Central Asian coins that circulated alongside those from the Han, Jin, Sui, Tang, Song, Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1911) dynasties. These coins trace the money trail that maps Dunhuang's path to becoming an international marketplace.