An oasis of time and memory

Dunhuang Museum is a wellspring of history and culture on the edge of one of our planet's most foreboding deserts, Erik Nilsson and Hu Yumeng report.

Silent centuries

But Dunhuang's prosperous rise was followed by its decline, and its fortunes scattered like dust in the dry wind.

Following the An Lushan Rebellion in the 700s, the Tubo regime seized control until homegrown hero Zhang Yichao restored Tang rule in 848 AD. In 1036 AD, the Xixia Dynasty captured the corridor.

Though the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368) briefly resuscitated trade, the Ming Dynasty eventually lost its grip on the region and sealed the Jiayu Pass in the 16th century, cutting off the last lifeline of its regional rule. An exhibited set of Ming chain mail stands as a silent guardian of the empire's futile attempt to shield its territory's rim.

Water again divined the tides of fate, when the Qilian Mountains' meltwater evaporated, desiccating the lifeblood that had fueled Dunhuang's pulse of commerce and culture. Meanwhile, sea routes became safer and cheaper trade arteries, redirecting the flows of goods from the backs of camels to the bellies of ships.

As commerce and water dried up, Dunhuang's population also withered, abandoning this metropolis to the Taklimakan for centuries.

The curtain fell, and a long intermission began.

Staging an encore

The Qing Dynasty reclaimed territories outside Yumen in the later years of Emperor Kangxi's rule (1661-1722). Dunhuang then slept until 1900, when Taoist priest Wang Yuanlu reawakened worldwide curiosity about these secluded ruins.

He unwittingly thrust the settlement into the global spotlight when he stumbled across the hidden chamber now known as the Library Cave, unearthing a trove of 50,000 manuscripts and paintings. Foreign explorers whisked many of these priceless artifacts overseas soon after.

The museum displays replicas of such scrolls as The Mahaparinirvana Sutra, The Carol of Hundred Thousand Verses and The Lotus Sutra.

This lost-and-found legacy sparked a call to rediscover and recover Dunhuang's heritage, setting the stage for an encore that's winning applause around the world.

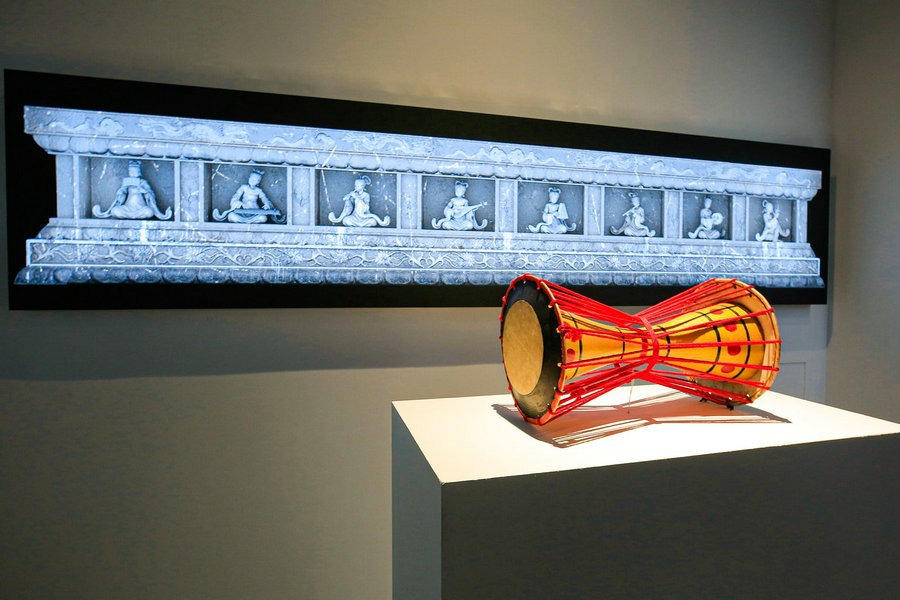

The museum's concluding displays portray ways that creatives are now bringing Dunhuang's motifs "out of the grottoes" and the past. For instance, they're integrating traditional fresco patterns like the nine-colored deer, thousand-handed Guanyin and triple-hare insignia into innovative designs for modern goods.

They are writing updated scripts for Dunhuang's sequel. They're carrying its Silk Road birthright into our globalized age, ensuring it isn't just inherited across bygone millennia but also by generations yet to come.

And so, the curtain rises again, as the Dunhuang Museum offers front-row seats to what this history means for our future.

Contact the writers at erik_nilsson@chinadaily.com.cn