Science teaching to foster curious minds

Guideline tells schools to get more hands-on with STEM subjects in the classroom

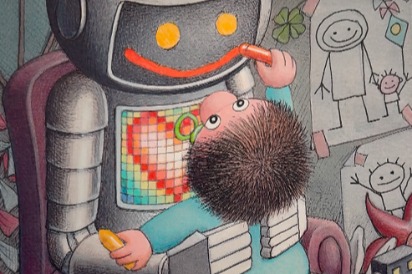

Science and technology education in primary and secondary schools is the focal point of a recently released guideline, aiming to nurture Chinese students who "think like scientists and practice like engineers".

The document was issued by the Ministry of Education and six other government departments on Nov 12.

Tian Zuyin, director of the ministry's department of basic education, outlined that by 2030, a structured science education system should be basically established in schools, with further improvements in curricula, teaching methods, evaluation mechanisms and teacher training.

By 2035, a full-fledged science education ecosystem should be in place, supported by social resources and widely applied project-based, inquiry-driven and interdisciplinary teaching.

Cultivating scientific literacy is a gradual and coherent process, Tian said. The guideline follows students' cognitive development, proposing a tiered approach. For lower primary grades, the focus is on experiential learning and sparking curiosity; for upper primary grades, conceptual understanding and hands-on exploration.

For students in middle schools, the key is on practical inquiry and technical application around real-world problems; and for high schools, experimental research and engineering practice are the focus, exposing students to cutting-edge advancements.

"We often ask children during field visits, 'What is your favorite subject?' They used to say physical education. We hope in the future they will say science," Tian said.

The guideline encourages schools to design their own plans based on their characteristics and student needs, integrating in-school and out-of-school resources. Pilot models such as "dual-teacher classes" — led by scientists and teachers together — and "future classrooms" using technologies like metaverse-based virtual labs are encouraged.

It calls for diversified assessment, combining process and outcome evaluation, to move beyond exam-focused metrics. A "digital profile" will track students' innovative growth, and scientific literacy will become a key part of holistic student evaluation.

Teacher training will be enhanced, with master's programs in science education at top universities and specialized training for current teachers. Experts from universities and research institutes will be encouraged to serve as part-time instructors in schools, according to the guideline.

As the policy rolls out, educators said that by making science more engaging, practical and inclusive, China can lay a solid foundation for a new generation of curious, creative minds ready to contribute to the country's scientific and technological future.

Lu Yongli, principal of Beijing No 2 Experimental Primary School, welcomed the guideline as a clear roadmap.

"Science education must start from childhood — it is foundational for the future," she said. Her school has established a labor and science education center to promote interdisciplinary integration and convert frontier scientific resources into teachable content.

Lu said that the national science curriculum already includes 78 compulsory inquiry experiments for primary students, reflecting strong alignment with the guideline's emphasis on blending science, technology, engineering and mathematics.

To address resource gaps, the guideline encourages collaboration among schools, universities, research institutes and tech enterprises. Lu's school, for instance, has invited scientists from Beijing University of Posts and Telecommunications and Tsinghua University to participate in course design and lab development.

Hu Guozhu, a science teacher at Yaoxiang Middle School in Dongan, Hunan province, shared his 24-year journey of fostering scientific curiosity. "In rural schools, science education was long marginalized," he said, describing how he has to meet students' curiosity in science with limited resources.

Recent local support has allowed his school to upgrade from a converted table-tennis room to a 300-square-meter smart robotics lab. Hu, now a national lawmaker, praised the guideline's emphasis on "adapting to local conditions". "Rural science education doesn't need to copy urban models. It can draw on local resources and address rural realities," he said. He advocates project-based learning and using national online educational platforms to help rural students engage in hands-on problem-solving.

Ni Minjing, director of the Shanghai Science and Technology Museum, said that science education should not just be about knowledge transmission. Its core lies in nurturing children's ability to observe phenomena, ask questions and develop scientific interest, he said.

Schools should create conditions for inquiry and guide students to pay attention to everyday things so that they can discover and solve problems, he said. Meanwhile, they need to reduce mechanical drill exercises and incorporate innovative activities into comprehensive student evaluations.

Zheng Qinghua, Party secretary of Tongji University in Shanghai and an academician at the Chinese Academy of Engineering, emphasized the role that universities should play in the ecosystem. Universities should lead in curriculum development, empower teacher training, and bridge resource gaps by opening labs and research centers to school students, he said.

He Shenggang, principal of Zhijin No 10 Primary School in Zhijin, Guizhou province, said the best science classrooms are life-based. "Vivid scenes in fields and yards are far more engaging than cold formulas," he said.

Guiding children to trace the paths of ants or record the timing of a rainbow is, in essence, teaching them to examine the world with an inquiring mind, he said. When educators bring the classroom into the real world, technology transforms from an abstract concept into tangible, lived experience. Students' curiosity is awakened, and their desire to explore is fully ignited — an outcome far more meaningful than rote memorization of facts, He added.

Xia Jun'an, a fifth-grade student at Xixing Experimental Primary School in Hangzhou, Zhejiang province, recently designed and built a water clock in a science class, inspired by ancient time measurement techniques.

His class first had to choose between an "outflow" and an "inflow" water clock. After lively group discussions and repeated revisions to their sketches, Jun'an and his classmates settled on an inflow-type model. Using simple materials like plastic bottles, they carefully pierced a hole in a bottle cap and assembled the parts.

The real challenge, he said, was marking the time scale. They tried two methods: timing each minute with a stopwatch to mark the water level and dividing the total water collected over 10 minutes into equal parts. "If the receiving bottle is too wide, the water level changes too slightly, and the scale becomes hard to mark accurately," Jun'an said.

Their first test failed because the hole was too large, causing water to flow too fast. Instead of giving up, Jun'an and his classmates analyzed the issue and found that both the hole size and water pressure affected the drip rate.

After carefully adjusting the hole, they tried again. "When the clock finally dripped evenly and timed three minutes successfully, it felt like I could 'touch' time — it was no longer abstract, but right there in the rhythm of each drop and the slow rise of the water," he said.

Through the project, Jun'an gained a deep appreciation for the ingenuity of ancient inventors, who created such tools without modern technology. The experience highlighted that learning science is not just about principles from textbooks, but about handson exploration, trial and improvement.

zoushuo@chinadaily.com.cn

- Science teaching to foster curious minds

- Hainan aims to become hub for global cultural exchanges

- 8 dead in residential building fire in South China

- Courts target child abuse done under guise of 'strict parenting'

- Shenzhou XXI astronauts conduct first spacewalk

- Openness, cooperation highlighted at dialogue